The book that sparked a global movement

The book that sparked a global movement

Written by David Batstone, Co Founder – Not For Sale

Finding slavery in my own back yard

Before Not For Sale became an organisation, it was a confrontation with reality.

Co-founder David Batstone discovered that human trafficking was taking place in a restaurant in his own community. What seemed like a distant global issue was happening locally, embedded in everyday life.

That discovery led to investigation.

The investigation became a book.

The book became a movement.

NOT FOR SALE

The Discovery that Changed Everything

– by David Batstone

For several years, my wife and I dined regularly at an Indian restaurant near our home in the San Francisco Bay Area. Unbe-knownst to us, the staff at Pasand Madras Indian Cuisine who cooked our curries, delivered them to our table, and washed our dishes were slaves.

It took a tragic accident to expose the slave-trafficking ring. A young woman found her roommates, seventeen-year-old Chanti Prattipati and her fifteen-year-old sister Lalitha, unconscious in a Berkeley apartment. Carbon monoxide, emitting from a blocked heating vent, had poisoned them.

The roommate called their landlord, Lakireddy Reddy, the owner of the Pasand restaurant where the girls worked. Reddy owned several restaurants and more than a thousand apartment units in northern California.

When Reddy arrived at the girls’ apartment, he refused to seek medical assistance. Instead, he and several associates wrapped the unconscious sisters in a rolled carpet and carried them to a waiting van. They then attempted to force the roommate into the vehicle as well, but she resisted and managed to prevent being taken.

A local resident, Marcia Poole, happened to be passing by in her car at that moment and witnessed a bizarre scene: several men toting a sagging roll of carpet, with a human leg hanging out of the side. She slowed down her car to take a closer look and was horrified to watch the men attempt to force a young girl into their van.

Poole jumped out of her car and did everything in her power to stop the men. Unable to do so, she stopped another passing motorist and implored him to dial 911 and report a kidnapping in progress. Thankfully, the police arrived just in time to arrest the abductors.

Chanti Prattipata sadly never regained consciousness; she was pronounced dead at the local hospital. A subsequent investigation revealed that Reddy and several members of his family had used fake visas and false identities to traffic potentially hundreds of adults and children into the United States from India. In many cases Reddy secured visas under the guise that the applicants were highly skilled technology professionals who would be placed in a software company. In fact, they ended up working as waiters, cooks, and dishwashers at the Pasand restaurant and other businesses that Reddy owned. He forced the labourers to work long hours for minimal wages, money that they returned to him as rent to live in one of his apartments. Reddy threatened to turn them in to the authorities as illegal aliens if they tried to escape.

The Reddy case is not an anomaly. Nearly two hundred thousand people live enslaved at this moment in the United States, and an additional 17,500 new victims are trafficked across our borders each year. Over thirty thousand more slaves are transported through the United States on their way to other international destinations. Attorneys from the U.S. Department of Justice have prosecuted slave-trade activity in ninety-one cities across the United States and in nearly every state of the nation.

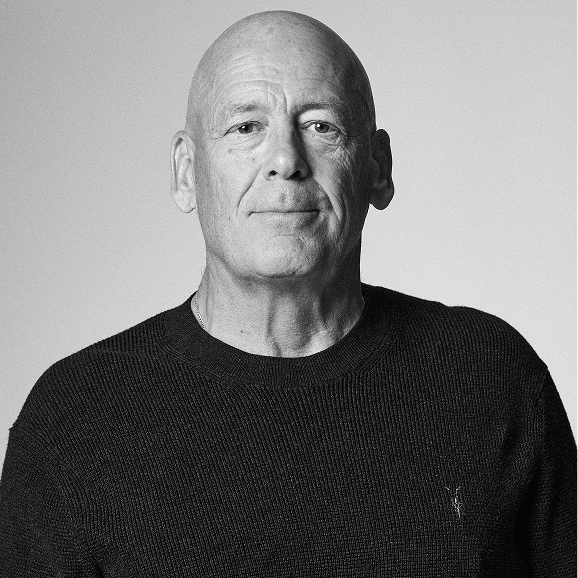

AUTHOR

David Batstone

David Batstone, Ph.D., is Professor of Ethics at the University of San Francisco and a leading voice on business ethics and social responsibility. His book Saving the Corporate Soul, and (Who Knows?) Maybe Your Own received the prestigious Nautilus Award for Best Business Book in 2004.

David serves as Senior Editor of the business magazine Worthwhile and was a co-founder of Business 2.0. He has appeared regularly in USA Today’s Weekend Edition as “America’s ethics guru,” offering insight on ethical leadership and corporate accountability.

As co-founder of Not For Sale, David continues to support and advise the organisation’s initiatives, contributing to its ongoing mission to address exploitation and strengthen community resilience.

Exposure to Action

The core insight of the book still guides our organisation today:

Exploitation is sustained by vulnerability.

Not For Sale’s work therefore focuses on:

• Strengthening economic resilience

•Supporting community-led initiatives

• Addressing systemic drivers of trafficking

• Building long-term prevention strategies

The book provided the framework.

The organisation became its practical application.