Mark Wexler: Illegal Mining Mekong Region: How Extractive Crime Fuels Exploitation of People & Planet

6.3 MIN READ

Introduction

When we talk about illegal mining in the Mekong region, we’re talking about more than minerals and markets. We’re talking about people. We’re talking about the fragile line that connects survival to exploitation and the river that binds millions of lives together.

Across the Golden Triangle — that region where Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar meet — an environmental and human rights catastrophe is unfolding. Unregulated rare-earth mining has poisoned rivers, torn through protected forests, and left communities struggling to survive. But behind every pit mine and toxic runoff lies something even darker: the exploitation of vulnerable people, especially girls, who become collateral damage in an economy built on extraction and silence.

At Not For Sale, we’ve learned that injustice rarely travels alone. When the planet is exploited, people are too. This is the story of a river under siege — and of the communities fighting to reclaim both their dignity and their future.

The Rise of Illegal Mining in the Mekong

Rare earths are essential for the modern world — the magnets in your phone, the battery in your car, the wind turbine spinning power to your home. But the cost of this convenience is hidden deep inside Southeast Asia’s darkest corners.

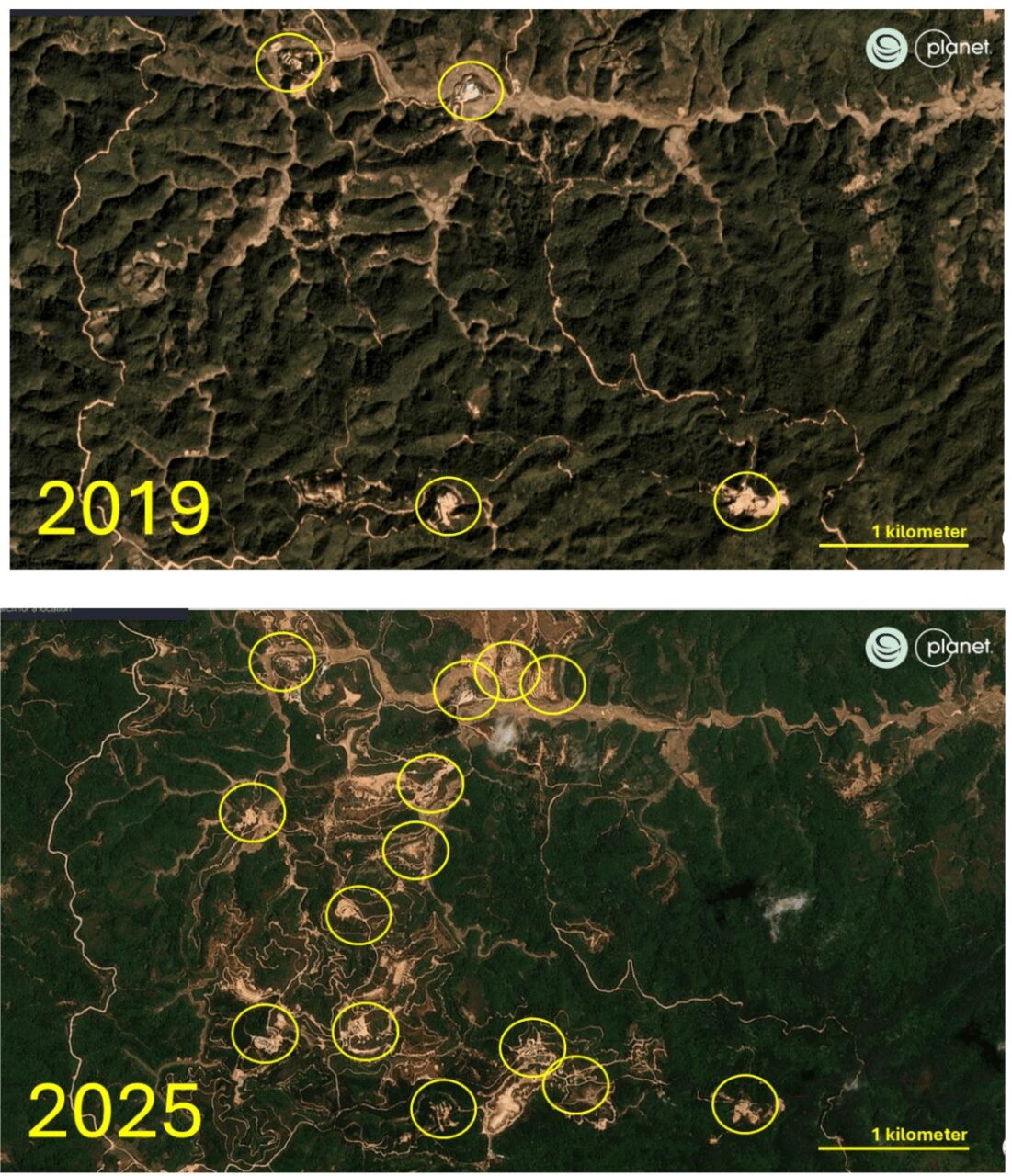

In northern Laos, rare earth mining has exploded despite an official ban. Satellite images show more than 27 mining sites carved into the hills, many inside protected “Gray Zones” and near tributaries that feed the majestic Mekong River. Toxic waste from these mines flows downstream, contaminating water, soil, and the very food people depend on.

Why does this happen? Incredibly weak oversight. Corruption. And foreign investors — often Chinese companies — “partnering” with local officials to skirt the rules. Laos, burdened by massive foreign debt, has become easy prey for extractive interests.

The Human Trafficking Pipeline Hidden in the Mines

Everywhere we see illegal mining, we see human trafficking and forced labor inextricably linked to it. The same goes for the Golden Triangle, these two forms of exploitation are twins.

Mining brings money in (in this case, mostly from China) and where money flows without accountability, people are bought and sold. In the unregulated areas that populate the borderlands, vulnerable people, many from indigenous Hill Tribes, workers arrive desperate for income. Many never return home. They are typically ethnic minorities, and refugees — and in many cases, girls — promised jobs that turn out to be bondage.

In Laos’s notorious Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone, casinos, trafficking, and mining overlap in a single economy of extraction. When rivers are poisoned and farms die, more families are forced to leave home. Those same families — displaced and desperate — are the ones most easily trapped by traffickers.

The cycle is cruelly simple:

Environmental destruction → economic desperation → exploitation → more destruction.

Breaking that cycle takes more than laws. It takes alternatives. At Not For Sale, we’ve seen the power of ethical business to rewrite this story. When people have opportunity and when they can earn, own, and lead with agency, exploitation loses its leverage. We’ve watched it happen in the Amazon, in Uganda, in The Netherlands. It can happen here, too.

Ecocide on the Mekong Tributaries

When you stand on the banks of the Mekong at dawn, the Laoian hillside erupts with golden hues and the river glows in the expanding light. But that glow now hides poison.

Across northern Myanmar and Laos, in-situ leaching, the process most used for rare-earth extraction, floods the earth with acid and heavy metals. That wastewater seeps into the tributaries that flow south to Thailand and Cambodia, carrying cadmium, manganese, arsenic, mercury, and others.

This is ecocide. The deliberate destruction of an ecosystem that sustains more than 50 million people. And ecocide is not separate from human trafficking or forced labour; it’s the same logic of disposability applied to nature and to people alike.When the river is dying, so are the livelihoods of those who depend on it. And when livelihoods disappear, traffickers move in.

Whenever I visit our project in northern Thailand, like I did just a few months ago, I meet young girls whose stories are living through this crisis. Their families once farmed fertile land near the border. Now, with polluted soil and no work, many are sent to find “jobs” — often in mines, cyber-crime compounds, or the sex trade.

This is what illegal mining in Southeast Asia does: it widens every existing fault line. Poverty. Gender. Statelessness. Climate. They all collide in the lives of girls too young to know what they’ve lost.

And yet every time we invest in education, in safe housing, in job training we see something powerful: resilience. These same girls become teachers, seamstresses, social entrepreneurs. They rise from exploitation to leadership.

That’s the core of our work at Not For Sale. We don’t just rescue; we rebuild. We don’t just protect; we empower. Dignity isn’t a gift, it’s a right. And in places where greed has stripped that away, dignity becomes the most radical act of all.

Conclusion

The story of illegal mining in the Mekong region is not just about the environment or the economy, it’s about the soul of a region. When rivers are poisoned and communities are hollowed out, we lose more than ecosystems; we lose futures.

But the opposite is also true. When we choose regeneration over extraction and when we invest in ethical supply chains, education, and enterprise we restore both people and planet.

The Golden Triangle doesn’t have to remain a symbol of vice and exploitation. It can become a model of transformation where economic growth honors the earth and protects its people.

If you believe that’s possible, join us.

Amazon Rainforest: Forced Labor, Mining and Deforestation

Global Initiative: Human Trafficking in the Mekong Region

UNODC/Nexus: Trafficking in Persons Research Review — Mekong Region

Published by NOT FOR SALE

Published October 31, 2025

Sign Up to our Newsletter

Join our movement and get the latest updates, stories, and ways to take action, straight to your inbox.